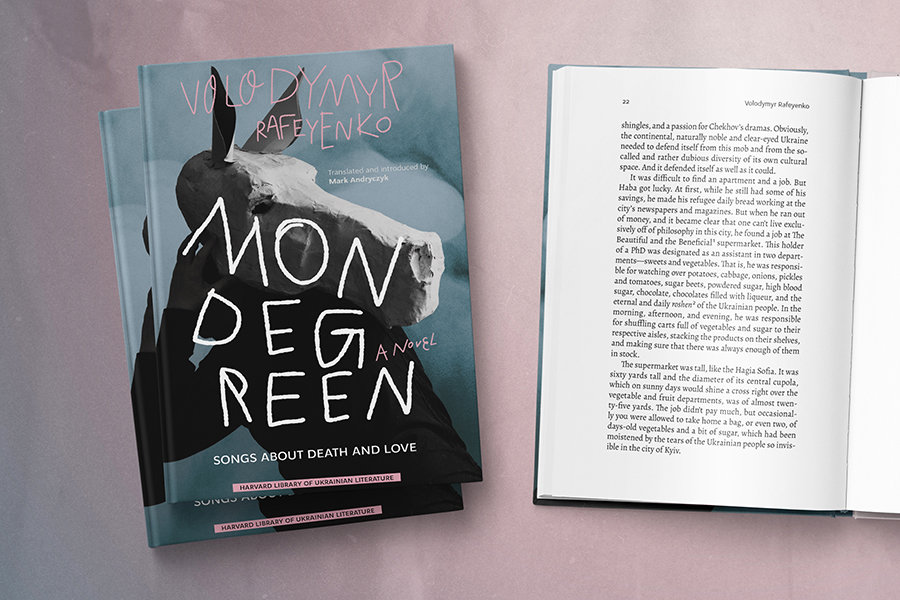

Meaning as a Projection of Soul – first essay by Ukrainian author Volodymyr Rafeienko

Celebrated Ukrainian author Volodymyr Rafeienko has published his first essay since being awarded a digital writing residency by the University of Chichester.

The two-time Russian Literary Prize winner, equivalent to the Booker Prize, is remotely engaging with students about his experiences of war. The digital residency was initiated by Reader in Creative Writing Suzanne Joinson from the University’s English and Creative Writing programme, recently ranked 2nd in the UK by the Guardian.

It is run in collaboration with the Rathbones Folio Prize and Stephen Spender Trust, and is supported through the UK/Ukraine Season of Culture by the British Council and the Ukrainian Institute. Volodymyr’s essay has been translated by Sasha Dugdale.

***

In every person’s life there are points when you realise things are coming together, being drawn into one. At such times it is as if you suddenly see the whole of your previous life in the sharp focus of a lens. This September, which began as unexpectedly as all the Septembers in the world begin, revealed to me the bitter and strange joy of the moment in which I found myself – by the will of the Gods, or perhaps the whim of fate.

I was born and raised in an industrial region in the East of Ukraine. As a provincial Ukrainian, I wrote and spoke Russian my whole life, and I lived surrounded by my family, my children, my parents and my friends. Suddenly everything changed: I found myself entirely on my own, and living in the capital Kyiv, under martial law. I was no longer writing or speaking Russian. And although I’d always lived here, in this country, at ease with myself and aware of all the circumstances of my life, I now had to make an effort to gather myself; to see clearly the true meaning of these days; to attempt to grasp at my own future. That is, of course, if I am to survive this autumn.

September brought cold nights and cooler days, and the particular nostalgic aroma of a land which still remembers the recent summer heat and the summer war of 2022. And although the summer is close, in the mind and on the ground still, time is moving forward and it is already autumn.

Air raid alarms sound day and night. The Russians launch missile strikes on peaceful towns, they destroy the civic infrastructure, kill women, children and old people. Nowhere in Ukraine is safe – the Russian world sends its violent message to every corner of the land – but Ukraine fights back, its capital Kyiv lives on, and I live on with it.

Every second of every day, I feel as if this bitter and terrifying time has been given to me, to my country as a turning point, a point when we can move to another plane of existence, another level of personal integrity. All through the last six months I have felt the way a piece of metal might feel as it is changing in the furnace into something which becomes itself only when it gains a distinct form of its own.

It seems to me that over the last few months we Ukrainians have been creating within ourselves and by ourselves the internal form of our own independent democratic state, a free and resilient European political nation. Through death, deprivation, the daily labour of war, the darkness and the decay visited upon our territory by the Russians, we will grow into something new, something never before seen in our many centuries of history.

Russians have been murdering us for hundreds of years, attempting to trample our language and culture into the dirt. They have treated us like a second-rate country. The Russian liberal ends where the Ukrainian question begins, or so goes a popular Ukrainian saying. Even the very best of Russians have, down to the level of their neural activity, an imperial brain wiring which only allows them to think of other nations condescendingly. This is especially the case in their relations with Ukrainians who have been trying to create their own state, and preserve their language and culture. Over the last three hundred years Russia has consistently tried to erase our cultural differences, to stamp on any small growth of Ukrainian culture, to wipe out even the mention of anything Ukrainian. In this sense what is now happening is simply the fruition of all these attempts. They are forcefully deporting the civilian population into Russia. More than two million Ukrainians have already been criminally abducted and taken into Russian territory – of these 200,000 are children. Russians aim their missiles at universities, museums, schools and medical facilities. This is genocide. And so far, despite our successes on the battle fields, nothing is decided, nothing is guaranteed. We are a non-nuclear state, and our army and our population, our industrial output and our currency reserves, the resources we have to put into victory: all these are many times smaller than that of our enemy. But still we fight and we win. We are chasing the enemy off our soil.

This is all happening thanks in large part to our allies. And of course, in the first instance, to Britain and the United States. But this war is our own national crucible: the furnace we must all pass through to become something different, quite different to how we were previously.

I am a tiny, barely visible part of my nation, but I am subject to the calls and the trials of these times in my own way. And these trials in turn mark the summation of a huge interval of my life and give it meaning, filling it with words and light. Through the pain of deprivation, the loss of contact with my loved ones, the chronic lack of a home, I am slowly growing into something different, something that is still myself, but for the moment is unknown to me.

My wife and I left our home eight years ago in 2014 when the Russians invaded our native Donetsk. We’ve lived in different places and seen a great deal. But the beginning of this year was perhaps the most genuinely terrifying time we’ve known.

All through January the world’s media, our allies, their security services and security experts were reporting that war would come. They were also sure that Ukraine would lose this war in a matter of days, if not hours. My wife and I wanted to believe right up until the end that none of this would come to pass. We’d already been displaced by the war eight years before and had wandered homeless since then, and we didn’t want to repeat what we had already undergone in leaving our home with a minimum of possessions and documents and setting out for the unknown. But there was no repetition – what happened was far, far worse than our departure in 2014.

On 24 February 2022, the first day of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, we were living outside Kyiv, in an area which was occupied by Russian forces. Our home was between Bucha and Borodyanka, two small towns where Russian soldiers behaved with particularly brutal cynicism and cruelty. Over the first few days the artillery sounded constantly, loud and very close. Our electricity and water was cut off. The shops, chemists and public transport stopped working. The internet connection disappeared. Russian soldiers rampaged in the small towns and villages close to the dacha settlement where we had been living for the last few years. It was dangerous to go out onto the roads as they were in constant use by Russian military vehicles.

There were days, in fact whole weeks, when we thought that the Russian army would take Kyiv. I’m understating it: in March this year, only a few months ago, I was completely certain that my wife and I wouldn’t survive. Every morning I would leave the dark, cold house, breath in the frosty March air, look deep into the turbid grey-blue sky and at the pine copse near the house, and the only thing I begged God for was a quick and honourable death for my wife and for me. Every day was the same. I did not think we would survive and I am still unbelievably amazed by the fact of being alive. Especially in the morning, when I open my eyes, I have to tell myself where I am, and why and who I am, and reflect on all this, on how to go on with all this in my head.

Although my battery was rapidly losing charge I was able to find a place in the woods where I could occasionally get mobile signal and I could ring my friend in Kyiv and tell him about what we were living through – and to ask for help. I knew that it was impossible for them to reach us by road. I knew that the so-called humanitarian corridors, even if they worked, were tens of kilometres away from us and we could never reach them on foot. I knew that there were no chances. But I had my wife with me back then, and everything I did, I did for her.

Perhaps it is because I made efforts only for her, sinking deeper and deeper into apathy on my own account and hardly believing in the possibility of success, that we were eventually lucky. At the end of March volunteers came and rescued us, at great personal risk to their own lives. The volunteers were utterly ordinary men not soldiers, actors working in Kyiv’s theatres, who used their own cars to pass through Russian checkpoints bringing medicine to the occupied areas, and then returning to safety with a few families, including my wife and me.

I remember passing through the checkpoints. I remember praying. I remember how the Russian soldiers looked at us, and how the low evening sun was reflected exactly and perfectly in the wing mirror of the car we were travelling in. As we drove along I thought that I would never again write in Russian. It had become impossible. Before the invasion I thought I could write in both Russian and Ukrainian together. Russian had been important to me, because my mother had spoken to me in that language and I had wanted to retain the link with a childhood in which the words ‘Russian’ and ‘murderer’ had not yet become synonymous.

Gazing out at the evening sky lit by the spring sunset, the destroyed homes and Russian military vehicles left standing between buildings in the villages we passed through and barely able to believe in the miracle of our rescue, I realised that I would never again publish work written in the language of a people who had perpetrated such horrors on our soil.

To say we were traumatised by these weeks spent in occupation is not to say very much at all. After a few weeks, my wife who was no longer able to bear the sound of air raids, went to the Czech Republic to live with our friends, and is still there. She won’t return until the war is over, and the war won’t be over this year, that much at least is clear. For the first time in many years I am almost completely alone. The vast majority of my correspondents live hundreds, some even thousands of kilometres away.

I have always led a fairly hermetic life, but now it is almost absolute, increased a hundredfold by the nightmare of war, and the horror that all of us living here must somehow come to terms with. I spend the days writing in Ukrainian, although even now this is hard for me, I think about life and I try not to lose heart. I believe that there is purpose in everything fate deals us and I am comforted by the thought that the will of our Maker is made manifest above all in the circumstances of our lives.

I have always led a fairly hermetic life, but now it is almost absolute, increased a hundredfold by the nightmare of war, and the horror that all of us living here must somehow come to terms with. I spend the days writing in Ukrainian, although even now this is hard for me, I think about life and I try not to lose heart. I believe that there is purpose in everything fate deals us and I am comforted by the thought that the will of our Maker is made manifest above all in the circumstances of our lives.

At some point I had the sudden realisation that everything that had happened to me over those months had pulled me together, brought me into myself and strengthened me as a person – as a free individual. It seems to me that I was always destined to reach this point in space and time. I needed the crucible of these days in order to at last become myself.

Our lives do have meaning, but the meaning of a life is only what we assign to the facts of that life; in effect projecting our soul on the world. In the effort to keep oneself on the point of thought, in the clear space of existence between the horror of war and the light of self-denial and faith, in the daily effort to remain human, to follow one’s principles – in all this is the slow and difficult birth of my country and indeed my own birth.

A new Europe is born in the flames of these days. Ukraine is not just fighting for herself. She is carrying out gruelling and important work in sanitising Europe from the horde of rats. For decades now they have misled us by pretending to share our human values, although in fact they never did.

Read more about author Volodymyr Rafeienko and his digital writing residency at the University.